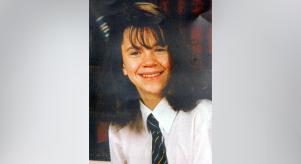

Janet Muller: what went wrong?

Some murder cases are easier to fathom than others. In true crime series When Missing Turns to Murder, we’ve explored honour killings, crimes motivated by sexual obsession, and instances of domestic abuse escalating to murder. All horrendous, but all at least presenting pieces of a grim jigsaw puzzle which police can put together.

But one particular case featured on the series – the killing of Janet Muller – still defies any conclusive explanation. The story of Janet, a young German citizen who’d been studying in Brighton at the time of her death, is scattered with question marks and is a startling indictment of the state of mental health services in this country.

In March 2015, Janet Muller was found at a bus stop, wearing only her night clothes. She had exhibited signs of mental distress in the lead-up to this moment when she was promptly sectioned and admitted to Mill View, a hospital in Hove for adults with mental health conditions.

A little over a week after this, Janet Muller escaped the hospital and disappeared. Her body was later found in the boot of a burnt-out, and a man named Christopher Jeffrey-Shaw was eventually jailed for manslaughter. But how did she end up in that car? What was her connection to Jeffrey-Shaw?

He maintained that he’d never actually met Janet Muller. He claimed he’d been totally unaware she was in the boot of the car when he was allegedly ordered to set it on fire by drug dealers, who’d supposedly used the car in a robbery. 'I am not getting done for something I haven't done,' he told police on his arrest. 'The whole thing is a nightmare I haven't woken up from.'

Yet, even more, disturbing is the question of why Janet was in harm’s way in the first place. How could it be that a girl with clear mental health problems, in a seemingly secure hospital, was able to simply depart and disappear without anyone realizing before it was too late?

The bare facts, revealed at the inquest, are damning. During her entire time at the hospital, Janet Muller told the staff she was desperate to leave. Indeed, on the very day she escaped, she’d already made an abortive attempt to flee the hospital, climbing over the garden wall (a wall which other patients had previously climbed, meaning the hospital was well aware of the risk).

She was found by a member of the public and brought back to the hospital, only to make her second escape just hours later. This was despite staff being told to keep her under close surveillance.

As the coroner bluntly put it, 'During her detention, Janet was at risk of absconding. Staff were aware, but there was a lack of communication… There were inadequate risk assessments carried out and documented. Nursing records, handovers, risk assessment and a care plan were incomplete, insufficient and at times contradictory.'

The failings in Janet’s care are depressingly familiar...

The trust apologized after the Muller case, and has since erected a 15-foot fence around the perimeter, as well as putting an enhanced entry and exit system into place. But Janet Muller’s fate is a stark reminder of the incessant problems plaguing mental health care. As her family solicitor has said, 'The failings in Janet’s care are depressingly familiar: inadequate risk assessments, poor record keeping and communication, a failure to respond promptly to known risks, and a failure to keep a vulnerable young woman safe.'

According to a recent Guardian investigation, at least 271 mental health patients have died over the last six years for reasons including inadequate supervision of people with known risk of suicide, and staff simply brushing aside the fears of relatives. All of which implies this isn’t a simple matter of not enough money being thrown at the problem. Indeed, even plush private mental health facilities have been hit with scandals.

The Priory Group, which has become famous for helping celebrities beat addictions, was fined £300,000 after a teenage girl, Amy El-Keria, died while in their care. She tied a scarf around her neck in her bedroom at a Priory hospital and died the next day. The establishment was later condemned for major lapses, including a lack of adequate staff training in CPR. Her furious mother spoke out, saying 'For 14 years we kept her safe but within three months with the Priory she was dead.'

Shocking cases have also been seen with care of the elderly. Last year, a care home company in Spalding was fined £70,000 after three residents put their lives at risk due to lack of security and risk assessments in the building. One 97-year-old woman was able to wander out of the home on a freezing February day and was found suffering from hypothermia. Not long after, an 81-year-old resident strolled out and was found by police wandering the streets.

Could such monumental mistakes be down to some inherent bias against patients who are old, infirm or mentally ill? After all, such patients are less likely to argue or raise the alarm if their care is clearly inadequate.

In a highly telling article, Wendy Burn – president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists – wrote of how mental health services are 'the poor relation of the NHS'. She also cited the still-relevant words of NHS founder Nye Bevan, who back in 1946 warned that 'the added disability from which our health system suffers is the isolation of mental health from the rest of the health services.'

Whether it’s down to lack of resources and funding, or – even more worryingly – old and mentally ill people being seen as docile, compliant and easy to ignore compared to patients who are physically ill, it’s clear that mental health care still isn’t being taken as seriously as it needs to be. The system has to change, in the name of Janet Muller and all those who’ve been so catastrophically let down.