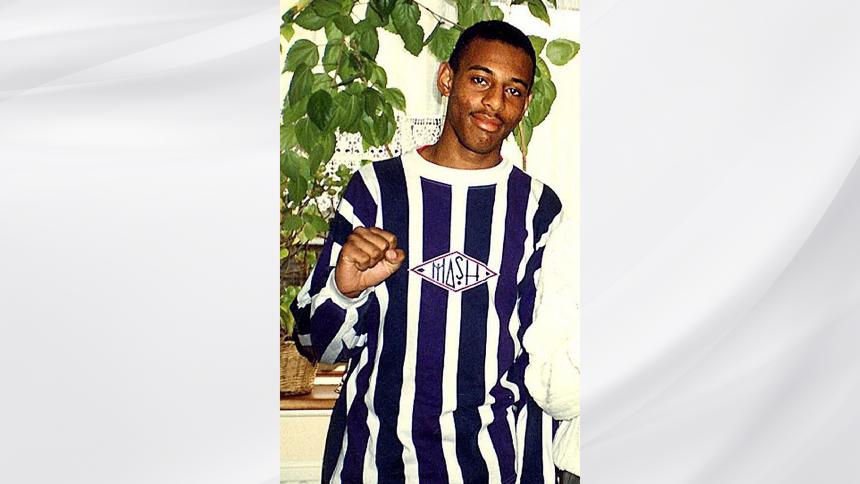

The murder of Stephen Lawrence

Stephen Lawrence was an 18-year-old sixth former when he was attacked on 22 April 1993. He and his friend Duwayne Brooks had been waiting at a bus stop in Eltham, London, when a gang of white teens shouted racial slurs at them, before attacking them. Though Brooks managed to escape unharmed, Lawrence was hit in the head with a bat and stabbed, leaving a 10-inch knife wound in his neck that caused arterial bleeding. The pair ran from their attackers, but Lawrence collapsed on the pavement. He died in hospital that same night.

The next day, a letter was left in a telephone box giving the names of the suspects in the attack: Luke Knight, Gary Dobson, brothers Neil and Jamie Acourt and David Norris, who had been linked with other racist incidents and knife attacks in the area. Norris had, in fact, stabbed Stacey Benefield only a month before Lawrence’s murder. All of the men were arrested and Neil Acourt and Knight were charged with murder after Duwayne Brooks had identified them.

The case brought a focus to racial tension in the area. Lawrence was one of four Black youths to be murdered in the area in two years. As 700 mourners gathered at his funeral service, there were calls for the British National Party to be closed, sentiments echoed by the clergyman presiding over the funeral. As the Anti-Racist Alliance also called for the BNP’s nearby headquarters to be closed, the party organised a march through London.

The tensions weren’t limited to those within the community: immediately, the investigation into the murder faced criticism. Brooks claimed that an officer at the scene threatened to handcuff him because he was becoming hysterical. Another questioned whether racial slurs were really used. The police came under fire for not immediately conducting house-to-house investigations along the street the killers escaped down. Two of the suspects even lived close to the scene.

Then in July, the charges against Acourt and Knight were dropped, as the CPS said Brooks’ evidence was unreliable. By April the following year, the CPS was refusing to prosecute, on the grounds on insufficient evidence. Neville and Doreen Lawrence launched a private prosecution against Neil Acourt, Dobson and Knight, but the judge ruled that Brooks’ identification evidence was inadmissible and the three teenagers were acquitted.

Almost four years after Stephen’s death, his inquest continued. All five suspects appeared, but refused to answer questions. The verdict came back as an unlawful killing in an ‘unprovoked racist attack by five youths’. The following day the Daily Mail ran the suspects photos on the front page, accusing them of Stephen’s murder and inviting them to sue if they were wrong.

But despite the inquest verdict, charges still hadn’t been made. Although an inquiry was opened in 1998, during which, all five suspects were ordered to appear and give evidence (and were duly pelted by protestors), it wasn’t until 2011 when two of the suspects, Dobson and Norris, were finally charged and sentenced to trial in the murder. They were found guilty in 2012.

So how did the five men evade charges for so long?

Fears of corruption hung over the investigation. John Davidson, who had been a senior detective on the first investigation, was accused of accepting bribes from Clifford Norris, the father of one of the suspects, in return for shielding the murderers. He was later cleared of the charges, though Duwayne Brooks said the investigation was pointless, calling Davidson a smokescreen.

It was later revealed that an undercover police officer had spied on Lawrence’s parents as they attempted to get police to properly investigate their son’s murder. The Black officer posed as an anti-racist campaigner for four years while he gathered information on the family. Nor were the Lawrences the only Black family targeted by Metropolitan police.

In 1997, Jack Straw opened an inquiry into his death: the Macpherson Report. It concluded that the investigation had been 'marred by a combination of professional incompetence, institutional racism and a failure of leadership'. Officers within the Metropolitan police force were named, the force was criticised, and specific recommendations towards tackling racism in society were recommended.

Over 20 years later, what has changed?

A number of the proposed changes in the Macpherson report were implemented—including legal reform allowing acquitted suspects to be retried if new evidence came to light. It was this that led to Dobson’s trial and then conviction. Targets for the recruitment of BAME officers were implemented. The police disciplinary and complaints system was overhauled.

But Neville Lawrence told the Guardian black people are still treated as ‘second-class citizens’ in Britain, saying the police remain institutionally racist. Black community advisers have claimed they were targeted by police. The BBC found that there is still a deep distrust of the police among young people, with both former Met officer and ex-chairman of the National Black Police Association Leroy Logan and Macpherson saying more needs to be done. Writing for The i earlier this year, Diane Abbot echoed these statements.

And let’s not forget, three of the five suspects in Stephen Lawrence’s murder have never been convicted for the crime. One is even thought to be living free close to where the attack happened.

Much might have changed in the 30 years since the teenager’s death, but it’s also clear that not enough has.