Lockerbie bombing: The investigation into Europe's deadliest terror attack

35 years on from Europe’s deadliest terror attack, questions still swirl over exactly who was behind the Lockerbie bombing. Here’s what we know.

The doomed flight

Just before 6:30pm on 21st December 1988, Pan Am Flight 103 commenced its journey from London to New York. The Boeing 747 was packed with hundreds of passengers, some having checked in at Heathrow, others having transferred from feeder flights, including a 727 from Frankfurt.

38 minutes into the flight, as the jet was over the Scottish town of Lockerbie, a bomb blew a hole in the fuselage, causing an uncontrolled decompression which tore the plane apart in seconds. Lockerbie’s residents heard a terrifying roar as fiery debris rained down upon them. 11 died on the ground, together with all 259 passengers and crew on the plane.

Piecing together the clues

The CIA quickly reported competing claims of responsibility that had been received. One was a caller who said the bombing had been carried out by a group called ‘the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution’ in retaliation for the destruction of Iran Air Flight 655, which had been shot down in error by a US warship earlier that year.

The terrible Iran Air debacle would certainly count as a strong motive for a corresponding atrocity like Pan Am 103, but the truth would only be determined through a painstaking examination of the wreckage. The priority was to find any debris which had been scorched, meaning that it had been in proximity of the bomb.

Shards of a brown Samsonite suitcase were found with such markings, along with charred fragments of clothing and a piece of a Toshiba radio cassette player. It was determined that a Semtex plastic explosive had been crammed inside the Toshiba device, which had then been packed with the clothes in the Samsonite case.

The Maltese connection

Investigators traced some of the charred fabric to a clothing manufacturer in Malta. Its books showed that a month before the bombing, garments later recovered from the wreckage had been supplied to a shop in Malta called Mary’s House.

The proprietor was Tony Gauci, who recounted how a peculiar customer had come to his shop sometime in the run-up to the bombing. The mystery customer, who appeared to be Libyan, stood out to Gauci because he’d bought an assortment of clothes without showing any interest in the sizes.

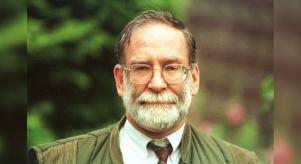

Gauci’s testimony was fundamental to the Lockerbie investigation, as he was asked to view numerous photographs of suspects and pick out the mystery customer from an identity parade. He selected Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, who had worked as head of security for Libyan Arab Airlines and was an alleged Libyan intelligence agent.

Convicting Megrahi

Another key piece of evidence implicating a connection to Libya was a fragment of the timer used to detonate the bomb. A Swiss company named Mebo was identified as the manufacturer, and it transpired that Mebo had sold a consignment of such timers to Libya’s intelligence services.

Eventually, indictments were issued for Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah, a station manager for Libyan Arab Airlines at Malta’s Luqa Airport. After years of legal wranglings over where the trial should take place, Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi agreed to release the men to face justice at a specially created court in the Netherlands, where the verdict would be reached by three judges rather than a jury.

While Fhimah was acquitted, Megrahi was found guilty of the murders of 270 people. The narrative of the attack, according to the official judgement, was that the suitcase containing the bomb was flown from Malta’s Luqa Airport to Frankfurt, where it was transferred onto the 727 feeder flight to Heathrow, where it was then transferred onto the doomed 747.

Megrahi unsuccessfully appealed the verdict, but was controversially released back to his native Libya on compassionate grounds in 2009 after being diagnosed with terminal cancer. He died in 2012.

Later developments

Journalists, legal experts and even some relatives of Lockerbie victims believe Megrahi suffered a miscarriage of justice. They point out that Gauci was an unreliable witness whose initial description of the mystery customer didn’t match Megrahi's. Gauci is also known to have seen his face in a magazine before picking him out of the line-up.

There’s also the issue of what date the mystery customer went shopping. It’s known that Megrahi was only in Malta on 7th December 1988, meaning that – if he was the culprit – the purchases in Gauci’s store must have happened on that date.

However, Gauci said that Malta’s Christmas lights were not up on the day the mystery customer came into his shop, implying the real date was earlier in the year, perhaps in November. What’s more, it was definitely raining on the day the mystery customer appeared, because Gauci remembered suggesting he buy an umbrella. Meteorology data shows that it was not raining in that part of Malta on 7th December 1988.

Despite question marks over Libya’s involvement, and alternative theories pointing to potential culprits like Iranian agents, the country was once again in the frame in 2020 when another Libyan was charged in connection with Lockerbie.

Abu Agila Mohammad Mas'ud Kheir Al-Marimi, currently in US custody, is accused of building the bomb and conspiring with Megrahi and Fhimah to carry out the attack. It’s alleged he confessed his role to Libyan law enforcement officials in 2012, soon after the fall of the Gaddafi regime. It remains to be seen whether his trial will shine much-needed light on the case that continues to generate such confusion and heated debate, almost four decades on.