History of the electric chair

On 6 August 1890, a convicted murderer named William Kemmler became the first person in history to be executed by electric chair. He took it calmly, with serene good humour. Moments before the current was switched on, he said ‘Take it easy and do it properly, I’m in no hurry’. But it was not done properly.

In the words of a New York Times article, ‘The execution cannot merely be characterized as unsuccessful. It was so terrible that the words fail to convey the idea.’ The horror of what happened to William Kemmler that day had a grim irony to it, because the electric chair had actually been developed as a more ‘civilised’ alternative to hanging. In fact, the man who came up with the idea, Alfred P. Southwick from Buffalo, New York, had a medical background, working as a dentist even as he developed the concept of execution by electricity.

The spark of inspiration in 1881, came after the peculiar death of a Buffalo dockworker called George L. Smith. At that time, a local electrical power plant had been actively encouraging citizens to tour the facilities, to dispel the fears and superstitions people still had about the strange new magic of electricity. Visitors soon realised they would experience an enjoyable tingling sensation if they touched the railings surrounding an electrical generator, and this became something of an unofficial attraction.

One night, after drinking for hours with his friends, George L. Smith clearly had a hankering for that tingling sensation. He broke into the plant and over-enthusiastically grabbed hold of the generator itself with both arms. He died instantly and was discovered by the staff, his corpse still clinging rigidly to the generator. To onlookers, it looked like Smith had died instantly and painlessly, without a mark on him.

Alfred P. Southwick had worked in engineering before he’d become a dentist, so was no stranger to electricity. He’d even experimented using low-voltage currents as a numbing agent for dental surgery. The George L. Smith case convinced him that the power of electricity could be harnessed for executions, and he began experimenting with the help of a doctor called George Fell, electrocuting hundreds of stray dogs in the Buffalo area. The experiments were crude but effective, sometimes involving coercing the dogs into boxes sloshing with water and wires. Dr Fell even dissected dogs while they were alive (and anaesthetised), to expose their hearts and lungs and see how their organs reacted when electrocuted.

The experiments were well-timed, as Southwick soon became a member of a commission set up by the New York state governor to look into alternative methods of execution so they could go beyond the ‘dark ages’ technique of hanging. They consulted doctors, lawyers and government officials throughout the state, pondering all kinds of alternatives, even the guillotine (which they dismissed as ‘utterly repugnant to American ideas’).

Shooting by firing squad was considered more suitable for military purposes. Lethal injection was another option, but doctors objected that it would cast syringes in a negative light and it was already hard enough to convince some patients to have injections. The idea of the electric chair eventually won out, partly because of an endorsement by one of America’s most renowned people: Thomas Edison.

When the famed inventor was first approached by the commission for his thoughts on the matter, Edison bluntly told them he would ‘join heartily in an effort to abolish capital punishment’. But soon after that he had an abrupt change of mind, helpfully suggesting that the best way to power an electric chair would be with a machine generating alternating current, such as ‘machines manufactured principally in this country by George Westinghouse.’

Westinghouse happened to be Edison’s arch-rival in the electricity industry. While Edison’s company was a purveyor of direct current (DC) electricity, Westinghouse’s firm specialised in alternating current (AC). The ever-cunning Edison wanted to dirty the image of AC by having it linked to death in the public’s imagination, so he wholeheartedly backed AC power for the electric chair. One of Edison’s colleagues even suggested the word ‘Westinghoused’ should be used to describe electrocution.

When the first electric chair was built, Edison’s people even saw to it that three Westinghouse generators scheduled for decommission were brought in to power the brave new killing contraption. Westinghouse himself tried to fight back by hiring a top lawyer to halt the execution of William Kemmler, the convict poised to become the first man to be ‘Westinghoused’. But it was to no avail, and on 6 August 1890, Kemmler – an alcoholic who’d killed his girlfriend in a drunken rage – was strapped into the chair.

The electrocution seemed to go according to plan, until horrified onlookers noticed Kemmler was still breathing after being given what should have been a fatal dose of electricity. ‘Have the current turned on again, quick! No delay!’ the attending doctor cried out. As more volts ran through Kemmler, blood vessels exploded under his skin and his hair began to burn. ‘Blood began to appear on the face of the wretch in the chair, it stood on the face like sweat,’ a journalist wrote. ‘An awful odour began to permeate the death chamber.

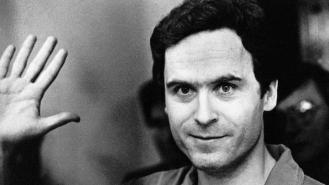

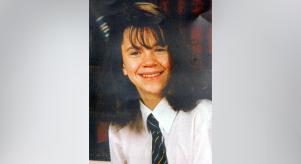

Despite this distressing start, the electric chair was soon adopted across different states as the favoured method of execution. A number of notorious killers have met their end in the chair, from Leon Czolgosz – the man who shot and killed US President William McKinley in 1901 – to the serial killer Ted Bundy. The chair also took the life of the youngest person ever to be executed in the US: 14-year-old African American child George Stinney, accused of of the murder of two white children in 1944. Stinney was convicted without any physical evidence, by an all-white jury. He was so small that he was made to sit on a Bible to fit into the electric chair properly. The mask, too large for his face, slipped off as the volts coursed through the child, showing his wet, wide-open eyes as he died. His conviction would be overturned in 2014.

As for the electric chair itself… It’s been displaced by lethal injection as the preferred means of execution throughout the United States, though it’s still an option in states including Florida and Tennessee, and controversy still exists over whether it may in fact be less painful and more humane than lethal injection.