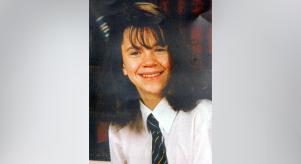

Shamima Begum: Victim or terrorist?

Shamima Begum was 15 when she left her home in London in 2015 and travelled to Istanbul to join ISIS and marry Dutch convert Yago Riedijk, a convicted terrorist. In the years since, Begum has tried to return to her home in the UK, but had her citizenship revoked. Now, courts have ruled that she will not be allowed back into the country to fight her citizenship case. But as a now 21-year-old who was only a teenager when she left the country, is Shamima Begum a terrorist or a victim of child grooming?

I don’t regret coming here

Four years after she left her London home, Begum was found in a Syrian refugee camp. She had had two children (both of whom had died) and was nine months pregnant with a third. Her husband was in captivity. She was 19. In an interview with the Times, she said, 'I’m not the same silly little 15-year-old schoolgirl who ran away from Bethnal Green four years ago.' She also said, 'I don’t regret coming here.' Her words go a long way to describing some of the complications surrounding her case. She might have been a child when she left the UK, but years later, she also stated that she didn’t regret her actions.

How much of a threat does she pose to the UK? Speaking to Sky News, she described her life in Syria as that of 'just a housewife' who stayed at home and looked after her children. She has said she never did anything dangerous, develop propaganda or recruit others.

At the same time, though, she has also spoken of seeing beheadings and being unaffected by it, of understanding the realities of IS rule and not questioning it. She has said she was 'Okay with it,' because as far as she knew, it was allowed under Islam. Her attempts to return to the UK have also come only after Islamic State was defeated. She wanted to return for the sake of her child.

Begum gave birth to her son days after giving her interview to the Times. Three weeks later and he died. His body was buried on the outskirts of the camp.

After his death, Begum spoke to the Times again. She said she had been brainwashed, that she 'really regretted everything' and wanted a second chance. Should she be able to get it?

For some, the answer is no: Begum should have to face the consequences of her actions. Her age at the time when she left London is negated by the fact that she went willingly and stayed for years, despite the pleas of her family to return.

There is also the concern of other ISIS prisonersmay attempt to return to the UK if Begum’s case is successful. That it could come with significant risks to national security.

For others, it is not that simple. Begum might have stayed in Syria as a legal adult, but she was still a child when she left.She was a victim of grooming, radicalised by videos she watched online that promised her she would be taken care of, that she could have her own family, lead the life she wanted under Islamic law. She wasn’t the first young girl to be radicalised. Nor is she the sole victim of grooming, but do we have more empathy for othersurvivors of child exploitation than we do for Begum because of her link to a terrorist organisation? How much does that factor into our feelings towards Begum and her personal responsibility?

Since her first interview in 2019 after she was found in the refugee camp, Begum has not appeared as the ‘perfect victim’. Initially, she denied regret, while claimingpeople should feel sympathy for her. All of that has worked against her.

Yet, we know Shamima Begum was a child at the time of her radicalisation, we know she—like other young girls—was vulnerable and had those vulnerabilities exploited. Do the four years she willingly stayed somehow negate that?

It is also possible to condemn her actions while believing she should maintain her rights as a citizen of the UK. For starters, the law is in her favour.

Revoking someone’s citizenship if it leaves them stateless is illegal under international law. When revoking Begum’s UK citizenship, the then home secretary Sajid Javid said she would be able to apply for citizenship in Bangladesh through her family—a country she has never been to. Bangladeshi officials have not only denied this, but have said she would face the death penalty there.

Begum was born in England and her mother is British. She is a British citizen. It was also in Britain that she was radicalised. Research might have shown that the reasons for radicalisation of women and girls is more complex than just love and marriage and that those that are radicalised are more than just passive victims. But it has also shown that feelings of social exclusion or discrimination faced at home can be a motivating factor, too.

There isn’t a simple answer for why it happens and it might not be right to negate these women and girls their autonomy over their own actions, but there’s also no denying this is a British problem, as well.

Shamima Begum might have been a child when she left the UK. She might have birthed and watched die her three children. She might be a victim of grooming who was radicalised at a young age. She might also have been complicit in her actions and a willing participant in her fate, until the end. She might not be the perfect repentant victim we would like her to be.

Regardless, she is British and stripping her of her UK citizenship denies her her legal rights. Ultimately, that speaks to something bigger than Begum herself.