Angels of death: The nurses who kill

They are the men and women we trust with our lives, but there are rogue medics who use their medical know-how to try and get away with murder. Each episode of Murder By Medic dissects the true story of a murderous physician as told by those who witnessed the case unfold.

Murder By Medic starts Monday, 19th August at 9pm on Crime+Investigation. The show will also be available to stream on demand and on Crime+Investigation.

Niels Högel

Niels Högel was already serving a life sentence for the murder of six people when the police started an investigation and found evidence of closer to 100 murders (although some think the number could really be closer to 300). He has since been dubbed Germany’s worst post-war serial killer and one of the most prolific in the world. He was also a nurse nicknamed ‘lifesaver Rambo’ by his colleagues and his victims were the people in his care.

Högel injected his patients with cardiovascular medication, which would induce cardiac arrest. He would then resuscitate them. It’s thought he did so to impress his colleagues by showing off his skills. However, many didn’t survive.

In 2005, he was caught injecting a 63-year-old patient and was arrested. It was only while he was on trial for the murder that other patients’ relatives came forward to accuse him. His victims ranged in age from 34 to 96.

Högel apologised in court but witnesses and experts have questioned his sincerity. Psychologists determined he had a 'severe narcissistic disorder' and one expert witness noticed an absence of guilt and shame. But as with all angel of mercy or death cases, there’s the question of why a medical professional, whose duty it is to help the vulnerable, would intentionally harm them? Högel’s case wasn’t unique.

Benjamin Geen

British nurse Benjamin Geen was not only found guilty of murdering two of his patients, but he used the same methods as Högel: injecting patients in order to resuscitate them.

We don’t like to think that the people that are put in place to care for us at our most vulnerable—the doctors, nurses and other medical professionals—are also the ones that could willingly commit murder. But the scary truth is that there are numerous instances of this happening. In a number of cases, these killers were able to commit several murders before they were implicated because the deaths weren’t questioned. Of healthcare serial killers, a study showed that 86% are nurses.

Beverley Allit

Beverley Allit, one of the UK’s most infamous female serial killers, was one of them. In the early 90s, Allit worked on the maternity and children wards at a hospital in Lincolnshire. While she was there, she murdered four children in her care by injecting them with insulin. She tried to kill another nine. Her youngest victim was seven weeks, her oldest 11 years old. The parents of one of them, Becky Phillips, were so grateful to Allit for her care that they asked her to be the godmother of Becky’s twin sister, Katie. Allit then injected Katie with overdoses of insulin and potassium, which left her with brain damage, partial blindness and partial paralysis. Allitt was diagnosed with Munchausen syndrome by proxy.

Unfortunately, there are no clear answers as to why these types of killers exist or what exactly drives a medical professional to abuse their role, though killers like Högel and Geen seemed to be motivated by a hero complex. We don’t even know whether the career choice is informed by their urges or if the desire to do harm is something that develops over time.

A career as a medical professional—a job that often requires years of training and to swear an oath to do no harm—can seem like an antithetical choice for those that go on to kill. But their profession can play into their crimes. Not only do they have a position of trust that they are able to exploit, but they have access to potential victims whom they have power over, as well as the drugs they often use to carry out their crimes.

Speaking to the BBC, professor of forensic psychology Katherine Ramsland said that very few healthcare serial killers enter the profession for that purpose, but are turned into killers. Professor of Criminology at Birmingham City University, Elizabeth Yardley, on the other hand, argued that it can be a combination of both cases: those who chose their profession for the access and those that began deliberately harming their patients while already working in healthcare.

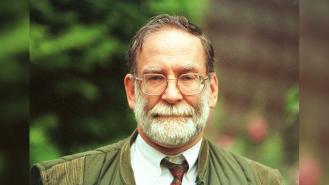

Donald Harvey

For the latter, one of the motivations to kill could be drawn from a sense of ‘mercy’: a wish to end the suffering of those they see as beyond help (whether this is the case or not). The American serial killer Donald Harvey quoted this as the reason behind the murders he committed. Harvey worked at a hospital as an orderly and is thought to have killed between 37 and 57 people (although he claimed 87). He described himself as an angel of death and said he did it to save his victims from suffering. His methods ranged from turning off ventilators and poisoning, to injecting patients with fluids tainted with HIV and putting a coat hanger into a catheter. When his attorney was asked why Harvey committed the crimes, he allegedly answered, 'Because he could'.

Barbara Salisbury

That admission can also give a clue for another motivation for healthcare serial killers: power. Harvey himself admitted at trial he played God and it’s thought that control is one of the main motivators for others, as well. Prosecution at the trial of Welsh nurse Barbara Salisbury spoke of her 'desire for control' after she tried trying to murder two elderly patients in 2002 in an attempt to free up hospital beds during a bedblocking crisis. She helped those she could and accelerated the deaths of those that weren’t going to survive, making the decision over the fates herself.

Though we may not know enough about healthcare serial killers’ motivations, experts are now aware of the warning signs to watch for. Hopefully, this will help people notice red flags before killers like Letby, Allit and Högel are able to go too far.